The Crewe Heritage Trail has been designed to offer you a guided route around Crewe Town centre highlighting some of the key historical buildings and archaeological sites. Follow the route on the map to each of the points and find the information below for each

Long before locomotives and engineering marvels, Crewe was little more than a scattering of fields and farmsteads. In fact, it’s mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086, where it appears as land held by Richard of Vernon. Historically, “Crewe” referred not to the town we know today, but to the nearby hamlet of Crewe Green. Back then, the area supported just a handful of households: a villager, two smallholders, and a rider, along with modest resources like meadowland, woodland, and two plough teams. Its annual value to the lord? Five shillings. A quiet corner of Cheshire, with no hint of the industrial powerhouse it would become.

Fast forward to the 1830s, and everything changed. The Grand Junction Railway Company arrived, laying tracks through open countryside and buying up land to build a new kind of town shaped entirely by steam, steel, and ambition. The nearby township of Coppenhall was chosen as the site for railway works, and soon after, Crewe began its dramatic transformation.

By the 1840s, the railway company had relocated its workforce to Crewe and started building not just homes, but a full civic infrastructure: churches, schools, assembly rooms, swimming baths, sewerage systems, and gas works. The layout of this new town was overseen by railway engineer Joseph Locke, a protégé of George Stephenson, the man often called the “Father of the Railways.”

Many of the buildings from this period still survive, tucked into the fabric of the town centre. They tell the story of Crewe’s rapid rise from rural obscurity to industrial significance, and they’re the stars of this heritage trail. Whether you’re a lifelong local or a curious visitor, we invite you to explore the architecture, ambition, and ingenuity that built Crewe from the tracks up.

The following checkboxes are used for accordion drop-downs. When selected, they show content that was visually hidden

Heritage

Tower of Christchurch

Rising above the streets of Crewe, the Tower of Christ Church is a proud survivor of the town’s Victorian past. Built in 1877 by engineer J.W. Stansby, this yellow sandstone tower is all that remains of the original Christ Church, whose brick-built body was designed by John Cunningham in 1843. Though the main church was gutted and lost its roof in 1978, the tower still stands as a testament to the ambition and craftsmanship of the era.

Its coursed rock faced rubble masonry gives the tower a sturdy, textured look. At each corner, tapering buttresses climb upward like architectural stilts, reinforcing the structure while adding a sense of vertical drama. At the west-facing entrance a chevron-patterned wooden door sits within a pointed Gothic arch, flanked by slender stone columns. Above it, a decorative hood mould curves protectively, its stop ends carved into expressive faces.

Just above the doorway, a large window with intricate geometrical tracery catches the light. On the north and south sides, the windows are arranged in two tiers: narrow pointed lancets below, and clover-shaped trefoils above, all framed within elegant blind arcades that hint at the grandeur once found inside the church.

Each face of the tower features a clock dial, set into panels of finely carved stone arranged in a subtle diamond pattern (diapering). These clocks once helped keep the town running on time and still lend the tower a sense of purpose.

Near the top, triple sets of louvred openings mark the bell stage, allowing sound to ring out across the town. These are divided by paired stone shafts with decorative rings, adding a touch of finesse to the functional design. The church was well known locally for the 10 bells ringing out for weddings and other important events.

Crowning the tower are octagonal pinnacles at each corner, rising like miniature turrets. Their surfaces are decorated with slender shafts and sunken lancet shapes, framing the stepped and gabled parapet above. The parapet itself is adorned with crockets, leafy stone curls typical of Gothic architecture, giving the whole structure a flourish of elegance.

In the 1970’s the roof was found to have dry rot so it was removed and services moved to The Lady Chapel, the brick structure still at one end of the ruins today. The church finally closed in 2013.

Whether you’re an architecture enthusiast or simply curious about Crewe’s past, the Tower of Christ Church offers a glimpse into the town’s Victorian spirit. It’s a landmark that has endured, inviting us to look up and imagine the stories it still holds.

Image shows the Christ Church prior to the roof demolition 1978, note crown like top of the tower (Cheshire Archives and Local Studies, Albert Hunn, C.14326).

Image shows the Christ Church prior to the roof demolition 1978, note crown like top of the tower (Cheshire Archives and Local Studies, Albert Hunn, C.14326).

Continue north along Prince Albert Street to point 2.

Heritage

Crewe War Memorial 1922

Standing quietly in Municipal Square, the Crewe War Memorial is a powerful reminder of the town’s enduring respect for those who served and sacrificed. Originally unveiled on 14th June 1922 by General Sir Ian Hamilton, the memorial was first placed in Market Square before being moved to its current location in 2006.

At its heart is a striking bronze statue of Britannia, a symbol of national strength and unity, designed by the renowned artist Walter Henry Gilbert. Gilbert’s work can be seen across the country, from the grand gates of Buckingham Palace to the reredos in Liverpool Cathedral, and his talent for blending dignity with detail is clear in Crewe’s memorial.

The statue stands atop a tall, tapering pedestal made from pale limestone, carefully cut and smoothed (known as ashlar masonry). The base features a rough textured band for contrast, and the whole structure rests on a square plinth surrounded by a paved area. Originally, this paved “well” was bordered by raised pavements with granite edges and decorative posts linked by chains, adding a sense of solemn enclosure.

Bronze plaques list the names of those lost in the First World War, and over time, the memorial grew to include those who died in the Second World War, the Falklands, the Gulf conflicts, and other theatres of war. These Roll of Honour plaques were once set into the surrounding pavement but were moved in 2006 to the sides of the pedestal itself, bringing the names closer to the heart of the monument.

Crewe’s War Memorial is more than just a piece of public sculpture: it’s a place of reflection, remembrance, and pride. Whether you pause here for a moment or linger to read the names, it offers a quiet connection to the stories and lives that shaped our shared history.

Image showing Crewe War Memorial in the original location of Market Square (Cheshire Archive and Local Studies, Albert Hunn, C.14283).

Image showing Crewe War Memorial in the original location of Market Square (Cheshire Archive and Local Studies, Albert Hunn, C.14283).

Archaeology

Mechanics Institute

In 1845 the Institution was founded by amalgamating an existing mechanics institute and a technical institute. It was formed to give technical training, in theory and practice to apprentices and workmen, and later had a more general educational role and included non-railway members. Its rooms in the assembly hall (later known as the town hall) originally contained just a library, news room and committee rooms. The committees of workmen reported to the directors, the library and news room had been brought together as one organisation at the end of 1844.

It was controlled by a committee of three members elected by the railway, nine elected by members from a list supplied by the railway and nine members from amongst themselves. From the 21 members there were three sub-committees; the first dealt with the running of the news room and library, the second with the classes and letting of the hall and the third with the public baths; horticultural exhibitions etc. The chairman or president was always the railway locomotive superintendent or in later years the divisional mechanical engineer or works superintendent.

In April 1936 the library and reading room were leased to Crewe Corporation for use as the public library but by the 1950s the buildings had deteriorated and they were demolished around 1970.

The Scientific Society was part of the Mechanics Institute. The Engineering Society, an independent body formed in 1879, closed in 1884 and deposited its minutes with the Crewe Mechanics Institute Library. Crewe and District Hospital Sunday Fund was responsible for forwarding church collections and other donations to selected hospitals, mainly those which treated local inhabitants. Its secretary was frequently the secretary of the Crewe Mechanics Institute.

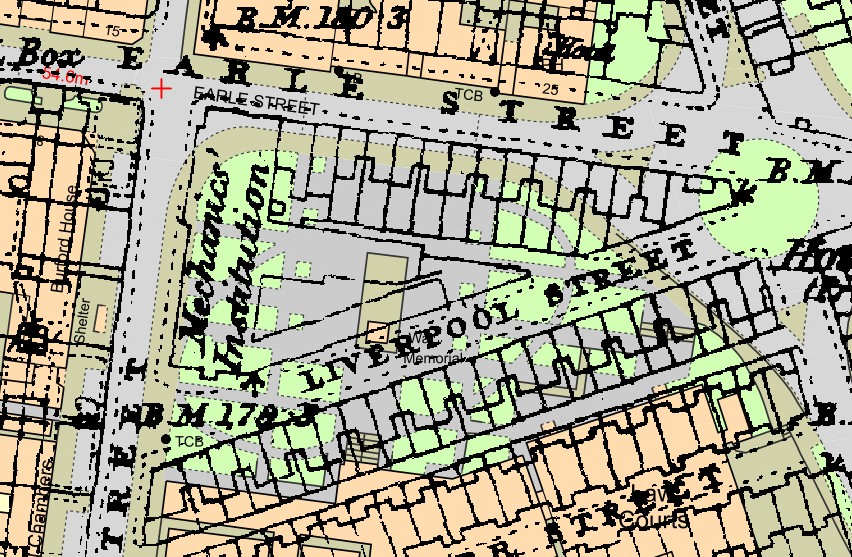

The location of Crewe Mechanics Institute overlaid on a current map (First Edition OS Map 1881).

The location of Crewe Mechanics Institute overlaid on a current map (First Edition OS Map 1881).

Carefully cross Earle Street and continue towards point 3.

Heritage

Market Hall

Crewe Market Hall isn’t just a place where goods once changed hands, it’s where the town’s ambitions first took shape. Built in the mid-19th century, likely on what were once open fields, this is the oldest surviving civic building in Crewe. It stands as a proud symbol of a town that was growing fast and thinking big.

At the time, Crewe was booming thanks to the railway. The Grand Junction Railway Company had arrived in the 1830s, and by the 1840s, Crewe had become a major hub for locomotive works. Iron, steel, and bricks were being produced locally, and the population soared from a few hundred to over 12,000 by 1865. The Market Hall was part of this transformation, built to support not just trade, but also new industries and better job prospects. It was driven in part by the Cheese and Agricultural Society, which aimed to diversify the town’s economy beyond the railway.

One of the most fascinating features of the Market Hall is its direct link to the railway itself. Tracks were laid right into the building so goods could be loaded and shipped with ease, a rare and clever design choice that shows just how closely Crewe’s identity was tied to the railways.

Architecturally, the Market Hall follows the Italianate style popular in the Victorian era, with red and yellow brickwork and stone detailing that still catch the eye today. While it has lost some original features like its roof structure, doors, and clerestory windows, it still holds architectural value. The survival of the Shambles (a traditional market area), the Market Hall office, and the original clock all add to its historic charm. And if you look closely, you’ll spot the arched opening where the railway once ran straight into the building.

Though no original architect’s plans have been found, records from the London and North Western Railway and the Crewe Local Board may hold clues about its early development and later changes. What’s clear is that this building played a key role in shaping Crewe’s civic and commercial life and it continues to stand as a reminder of the town’s bold beginnings.

The Municipal Buildings

If you’re strolling through Crewe and spot a building that looks like it could have been plucked straight from a grand European city, you’ve likely found the Municipal Building. Built between 1902 and 1905, this impressive structure was designed by architect H.T. Hare in a style known as English Baroque. A bold, theatrical look that was all the rage for important public buildings at the time.

Made from warm yellow sandstone and topped with a slate roof, the building has a commanding presence. It’s arranged in five sections, or “bays,” with the central three set slightly back, framed by towering stone columns that wouldn’t look out of place on a Roman temple. These columns are Ionic in style (look for the scroll-like shapes at the top) and they give the building a sense of grandeur and formality.

The entrance is equally dramatic: a deep, rounded archway with ornate wrought iron gates and a handsome oak screen with double doors. On either side, you’ll see timber framed windows with arched tops and decorative stonework, including carved keystones shaped like cartouches (think scroll-like frames). Above the central openings, keep an eye out for the reclining stone figures sculpted by F.E.E. Schenck. An artistic flourish that adds personality and flair.

On the first floor, the windows are framed with stone surrounds and flanked by small balconies with curved brackets. Higher still, dormer windows peek out from the roof, topped with little triangular pediments and fronted by a stone balustrade that adds a touch of elegance. At the ends of the building, round “bullseye” windows are decorated with egg-and-dart moulding and stone garlands, known as festoons.

The roofline is finished with stone coping, chimneys, and a charming cupola (a small dome-like feature) topped with a weathervane shaped like a locomotive - a nod to Crewe’s proud railway heritage.

Step inside, and the grandeur continues. The entrance hall features classical Tuscan columns, and a beautifully patterned staircase made from York stone. In the Council Chamber, you’ll find marble Ionic columns and a large Venetian-style window that floods the room with light. The doors are made from rich hardwood, set in elaborate frames, and the plasterwork throughout is decorated with traditional motifs like festoons and egg-and-dart moulding.

This building isn’t just a place for council meetings, it’s a celebration of civic pride, architectural ambition, and Crewe’s place in the story of modern Britain.

Interior image of Municipal buildings.

Interior image of Municipal buildings.

Different interior image of Municipal buildings.

Different interior image of Municipal buildings.

Turn left on Earle Street and immediately right onto Hill Street. Continue on Hill Street towards point 4.

Heritage

Lyceum Theatre

If buildings could take a bow, the Lyceum Theatre would be centre stage. First opened in 1887 and substantially rebuilt in 1910 by local architect Albert Winstanley, this red-brick beauty has been entertaining Crewe for well over a century. The theatre had to be rebuilt after a serious fire and is believed to be Cheshire’s only Edwardian Theatre.

The theatre’s bold façade is built from deep red Accrington brick, with a slate roof and a dramatic gable that proudly displays its name and date in a large plaster panel. It’s three storeys tall, with five main sections across the front, and an adjoining wing to the east that once housed the theatre’s offices. The design is full of character, with brick columns (called pilasters) dividing the front into vertical slices, and decorative terracotta detailing that adds warmth and texture.

Look closely and you’ll spot a mix of sash windows, some grouped in threes, others standing solo, all framed with moulded terracotta sills and keystones. The central bay features a wide arched window (called a lunette) above a pair of sash windows, giving the building a sense of symmetry and grandeur. The roofline is finished with a neat stone coping and capped pilasters, while the east wing adds its own flair with Caernarvon-style window heads and a decorative cornice.

Step through the doors, there are four pairs leading into the auditorium and two and a half pairs into the foyer and you’ll find yourself in a space that’s every bit as theatrical as the performances it hosts. Inside, the auditorium features a dress circle, gallery, and private boxes, all fronted by lavish plasterwork. Expect to see ornate cartouches and reclining figures sculpted in relief, adding drama to the décor.

The proscenium arch (the grand frame around the stage) is richly decorated, and the ceiling boasts a large plaster rose that draws the eye upward. Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel (of Laurel and Hardy fame) have performed on the stage here and according to the theatre the stage floor is reinforced because an elephant nearly fell through it! It’s a space designed not just for watching theatre, but for feeling part of something special.

The theatre was extensively refurbished in the early 1990’s and reopened by Queen Elizabeths II’s sister Princess Margaret.

The Lyceum has long been a cultural cornerstone of Crewe, and its architecture reflects the town’s pride in performance, creativity, and civic life. Whether you’re catching a show or simply admiring the building, it’s well worth a standing ovation.

Archaeology

Lyceum Square

The area of Lyceum Square has a number significant archaeological deposits surviving below the surface. There are several buildings noted on the 1881 First Edition Ordnance Survey Map of the area, showing the density of the development of early Crewe.

There are two chapels, a school and a public house. The first chapel, St Mary’s Roman Catholic Chapel, is now the location of Lyceum theatre, although few archaeological deposits relating to St Mary’s are now thought to survive below the Lyceum Theatre. To the north of the square is the site of the of Wedgewood Chapel, a methodist chapel directly opposite St Mary’s Chapel. Wedgewood Chapel had a small school within the complex of the structure. It is very likely that the foundations of the Wedgewood Chapel remain, sealed beneath Lyceum square.

Early Lyceum square overlaid on a current map (First Edition Ordnance Survey Map 1881).

Early Lyceum square overlaid on a current map (First Edition Ordnance Survey Map 1881).

Exit Lyceum Square by Heath Street, continue across to Victoria Street, heading west toward point 5.

Archaeology

Former Bus Station

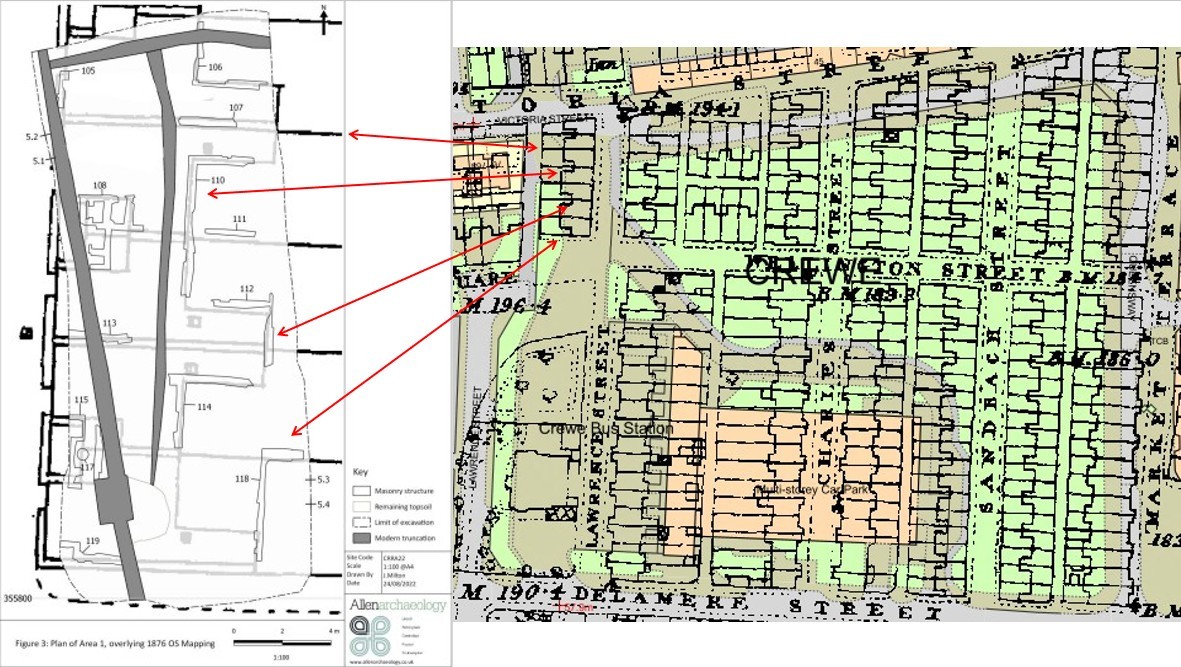

The former bus station was subject to a planning application to remove the old bus station and create a car park and new station. As part of these works, an archaeological evaluation was request as a large amount of early workers housing was seen on the 1881 First Edition OS Map.

While most of this housing was destroyed during the construction of the bus station, a small pocket of land was left undeveloped during the life of the former bus station. This patch of land held a prefabricated structure which had no below ground footings and therefore, sealed and protected the archaeology beneath.

During the evaluation the foundations of several houses within this patch of land were uncovered. Along with the drainage systems for the houses. Given the high level of development around this area of Crewe town centre, the level of preservation of these foundations were relatively unique, showing that while development has been dense in the centre of Crewe, below ground archaeological remains can and do survive.

On the left of the image is the drawn plan of the evaluation trench, provided by Allen Archaeology, on the right is the 1881 First Edition OS Map Overlay on the current map to show the location of the trench and its features (walls).

On the left of the image is the drawn plan of the evaluation trench, provided by Allen Archaeology, on the right is the 1881 First Edition OS Map Overlay on the current map to show the location of the trench and its features (walls).

Continue west along Victoria Street, toward point 6.

Heritage

Victoria Street

Just off the bustle of central Crewe, Victoria Street offers a quiet glimpse into the town’s railway roots. Built around 1850 by architect John Cunningham, this row of eight houses was originally commissioned by the Railway Company to house its workers back when Crewe was rapidly transforming into a major railway hub. Today, the buildings have been cleverly adapted into sixteen private homes, but they still carry the character of their industrial past.

Victoria Street itself is one of the two original routes that existed before the town was formally laid out, making it a rare surviving thread in Crewe’s early landscape. The houses here represent the last row built by the railway companies for their workers and are known locally as ‘Gaffer’s Row’, likely a nod to their senior roles in the railway hierarchy.

Constructed from warm brown brick and topped with classic slate roofs, the houses are modest but full of thoughtful detail. Each one has a small single-storey porch that juts out from the front, with a rounded archway and a steep stone slab roof. These porches originally framed four-panel wooden doors, each topped with a simple fan-shaped window to let in a little light.

The windows are traditional sash style, with stone sills and subtle brickwork arches above. If you look closely, you’ll notice that the window spaces above the porches have been filled in, likely part of later changes to the buildings. The roofline is finished with a neat brick cornice that supports the guttering, and the chimneys are particularly striking: each one has four square flues, grouped together and capped with projecting stone tops. It’s a small detail, but one that adds to the rhythm and symmetry of the street.

Over the years, the houses have been extended at the back using reclaimed bricks, keeping the look consistent and respectful to the original design. Inside, new porches have been added behind the front doors, allowing each original entrance to serve two homes side by side, a clever solution that preserves the historic façade while adapting to modern needs.

Victoria Street is more than just a row of houses. It’s a snapshot of Crewe’s working-class heritage, built during a time when the railway was reshaping the town and offering new opportunities. These homes once buzzed with the lives of railway workers and their families, helping to build the Crewe we know today.

Continue west along Victoria Street, turning left on to Gatefield Street. Continue down Gatefield St towards point 7.

Heritage

St Mary’s Catholic Church

Tucked away in Crewe’s townscape is St Mary’s Catholic Church, a striking red-brick building that’s been part of the community since 1891, following 5 years of fundraising. Designed by the celebrated architectural firm Pugin & Pugin, whose name is practically synonymous with Victorian Gothic style, St Mary’s is a fine example of how faith, craftsmanship, and civic pride came together in the late 19th century.

From the outside, the church is full of character. Its tall southwest tower rises with confidence, supported by angled stone buttresses that narrow as they climb. The windows are a mix of styles: geometric shapes at the lower levels, slender pointed lancets higher up, and large louvred openings near the top to let the sound of bells ring out. The roof is steep and pyramid-shaped, with little triangular windows tucked halfway up like architectural eyebrows peeking out from the slope.

The entrance is through a porch that’s both sturdy and elegant, with a pointed arch framed in stone and topped with a cross. The wooden door is made from thick planks and iron fittings, giving it a medieval feel. Above and around the church, you’ll spot a variety of window shapes: some with flowing tracery, others with simple quatrefoils (four-leaf designs), all set in stone frames that add texture and rhythm to the building’s façade.

Inside, the church is just as impressive. Rows of octagonal stone columns line the aisles, supporting graceful arches that lead your eye toward the altar. The ceiling is panelled and richly detailed, with carved stone supports (called corbels) holding up the wooden beams. The chancel, the area around the altar, is framed by elegant arches and filled with light from tall windows.

The focal point of the interior is the reredos behind the altar: a gilded stone screen decorated with classic Gothic motifs like dagger shapes, leafy crockets, and ornate brattishing (a kind of decorative cresting). Above the tabernacle sits a baldacchino, a canopy supported by polished marble columns, that adds a sense of ceremony and reverence. On either side are stone altars and separating the nave from the sanctuary is a marble communion rail carved with religious symbols.

Even the Stations of the Cross lining the walls are thoughtfully crafted in moulded plaster, each one telling part of the story of Christ’s final journey.

St Mary’s isn’t just a place of worship, it’s a beautifully designed space that reflects the artistic and spiritual values of its time. Whether you’re drawn to its architecture, its history, or its quiet atmosphere, it’s well worth stepping inside and taking a moment to appreciate the detail.

Continue south on Gatefield Street, turning left onto Delamere Street. Point 8 is directly opposite the junction of Gatefield Street and Delamere Street.

Heritage

47 Delamere Street

This handsome mid-19th century house has worn many hats over the years. Built around 1850, this house was originally the home of a railway manager back when Crewe was booming as a centre for locomotive engineering. Today, it’s a convent, home to a small community of nuns, but its architecture still whispers stories of Victorian ambition and railway prestige.

The building is made from a mix of red and brown brick, with a classic slate roof and a layout that’s both practical and full of character. It has two main storeys plus an attic, and its front is divided into three bays. The entrance is marked by a timber porch with square posts and a gently arched opening. Step closer and you’ll see a traditional four panel door with glazed sections and side windows, topped by a rectangular window that lets in extra light.

On the northeast side, the red brick gable features a pair of recessed sash windows with stone sills supported by decorative corbels. Above them is a striking five window oriel, a kind of bay window, held up by a cluster of brackets and topped with a hipped roof. Stained glass panels add a splash of colour, and short gable boards frame the roofline like a picture.

The western side of the building is made from brown brick with blue bands running through it, a subtle but stylish touch. There’s a hexagonal bay window here, with stone framing and a low ornamental railing around the roof. Upstairs, the windows are topped with Caernarvon-style arches, and above those, you’ll spot pointed Gothic arches with decorative stone panels carved with leafy designs.

Even the attic window gets in on the act, with its own Gothic arch and stone detailing. The west gable is finished with a stepped arrangement of corbels that appear like a little staircase carved into the brickwork, adding a flourish to the roofline.

Though it may look like a quiet residence today, 47 Delamere Street is a rare surviving example of the kind of housing built for railway officials in the mid-19th century, and it offers a glimpse into the lives of those who helped shape Crewe’s industrial story.

When viewing this property please remain on the public footpath.

Continue east on Delamere Street, turning right on to Lawrence Street. Follow Lawrence Street round to the left on to Chester Street.

Archaeology

Chester Place

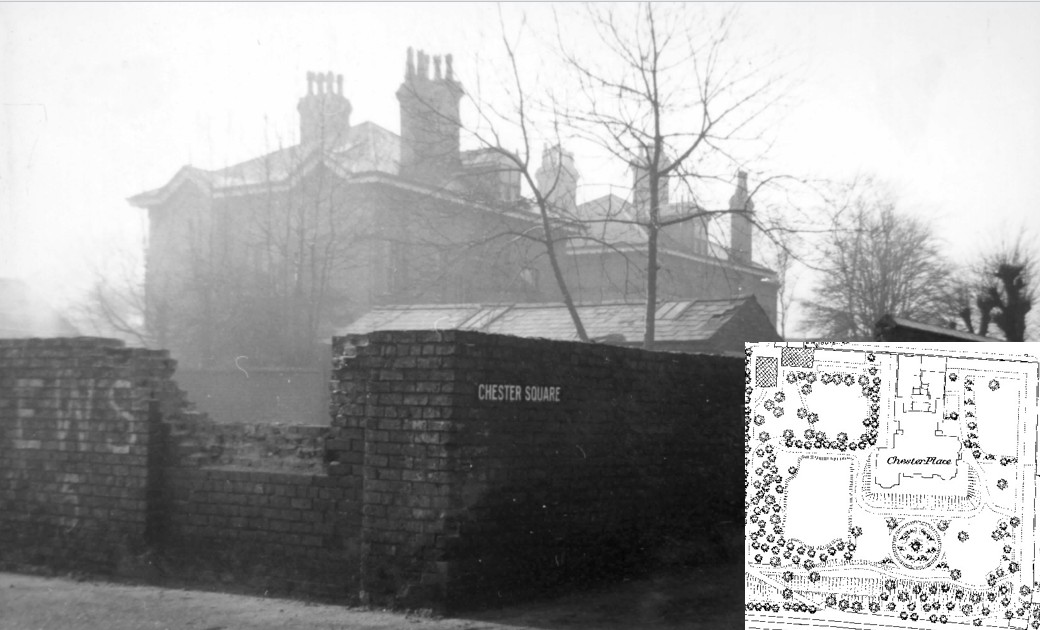

A large villa is seen on the 1881 First Edition 25” Ordnance Survey Map of Crewe located to the south of the junction of Chester Street, Lawrence Street and Chester Square. This mansion and garden spread over a 1.2 acre plot in the centre of Crewe. Chester Place was home to Francis William Webb during the mid 19th century. Webb was the chief Indoor Assistant (Works Manager) and taught at the Mechanics Institute. Webb was heavily involved in the development of Crewe, serving as Mayor and initiating projects such as the Cottage Hospital and Queens Park.

Following Webbs occupation, Chester Place was home to a string of superintendents and was located very close to the workers houses.

Chester Place was demolished in the 1960’s and was levelled, tarmacked and the Crosville Social Club was constructed. It is likely that there are significant below ground remains of Chester Place, particularly the cellars, in the area of the undeveloped car park.

Image of Chester Place prior to demolition (Cheshire Archives and Local Studies: Alert Hunn:c05715) inset with a plan of Chester Place taken from the 1875 Crewe Town Plan, showing the garden details.

Image of Chester Place prior to demolition (Cheshire Archives and Local Studies: Alert Hunn:c05715) inset with a plan of Chester Place taken from the 1875 Crewe Town Plan, showing the garden details.

Continue east on Chester Street towards point 10.

Heritage

Chester Street Cottages

Built around 1848, this charming row of nine cottages on Chester Street is a quiet reminder of Crewe’s railway beginnings. Designed by architect John Cunningham as part of engineer Joseph Locke’s original town plan for the Grand Junction Railway Company, these homes were part of a larger vision to house the workers who helped build and run the railway that transformed Crewe into a thriving industrial town.

Today, they’re private dwellings, but their original character still shines through. Made from brown brick and topped with neat slate roofs, each cottage has two storeys and a symmetrical layout. They were built in “handed pairs”, meaning each pair mirrors the other, with distinctive Tudor-style arched porches flanking a central gable. These porches once sheltered simple entrance doors, now replaced with multi-panel versions that still suit the building’s style.

Above each porch, you’ll spot a single small window tucked into the gable, while the main windows are wider, horizontally sliding sash types, designed for practicality and ventilation. All are framed with stone sills and subtle brick arches. Look closely and you’ll see a small blank panel set into the top of each porch gable, surrounded by chamfered brickwork, and finished with a narrow, slightly shaped barge board. A decorative flourish at the roof edge.

The roofline itself is full of detail: moulded fascia boards support the gutters, and the ridges are lined with blue tiles. Tall chimney stacks rise between the cottages, each with four flues grouped together and capped with stone, a feature that once served multiple fireplaces inside.

These cottages weren’t built in isolation. Similar terraces on Betley Street and Dorfold Street were part of the same development, forming a network of railway housing that gave Crewe its distinctive Victorian character. Though modest in scale, they reflect the care and planning that went into building a town from the tracks up.

Whether you’re admiring the brickwork or imagining the lives of the railway families who once lived here, Chester Street offers a quiet but meaningful finish to Crewe’s heritage trail.

Continue east on Chester Street, crossing Market Street and Prince Albert Street, arriving back at point 1 Christ Church. Crewe Lifestyle Centre is to the right.